TERRE HAUTE, Ind. — An Indiana man who was found not guilty by reason of insanity in a 1973 kidnapping and murder, and who was subsequently killed by police during a botched kidnapping five years later, has been named as the prime suspect in the brutal 1972 slaying of an Indiana State University coed.

Terre Haute Police Chief Shawn Keen announced Monday that DNA evidence and familial genealogy has revealed Jeffrey Lynn Hand as the likely killer of Pamela Milam. Milam, 19, was last seen alive the night of Sept. 15, 1972, following a sorority event on campus.

The ISU sophomore was found bound and gagged in the trunk of her car the following day by her family. She had been strangled.

DNA found at the crime scene matched DNA samples from Hand's two sons with a 99.9999% probability of paternity, Keen said during a news conference. Before his death in 1978, Hand had a long and violent criminal history that included homicide, stalking and kidnapping, the police chief said.

"Based on genetic genealogy, he's in the only position in the family tree to be my suspect," Keen said. "He has a history not only of stalking or selecting his victims from Terre Haute, but also killing them."

Keen said he had been investigating the cold case since 2008, long before becoming police chief last year.

Charlene Sanford, Milam’s oldest sister, thanked Keen for reopening her sister’s case, saying she’s not sure her family ever thought they would see it solved. She said his meticulous work and determination made it possible.

"It's been a long 46 years, seven months and 20 days," Sanford said Monday. "Many of us, as we got older, thought we would die before we ever learned who had killed our sister."

"We were happy to know he hasn't been out there living a great life for 47 years.”

Sheila Milam, who, along with her father, discovered her sister’s body, also spoke after the news conference.

"Losing her was like losing part of my body and my soul," Milam said.

Milam said she wished her parents had lived to see her sister’s killer identified.

Keen apologized for his nearly hour-long presentation of the case but said he did so in the hopes that other law enforcement agencies would utilize the tools through which Pam Milam’s murder, Terre Haute’s oldest unsolved case, was solved.

"This type of genetic genealogy can really help other cases," Keen said. "I feel that there's other jurisdictions that have these cases, I think there's other families that are waiting for answers, and I think that applying the science -- it's a shame if we don't try."

A heartbreaking discovery

Keen made a point during Monday’s news conference to talk about who Milam was.

"So many times in these cases, the suspects begin to overshadow the victims, and we forget who they were," Keen said. "So, as I go through this case, please think about who the victim is in this."

Pam Farris, who said she was a classmate in Milam's honors courses, asked Keen on the department's Facebook page to tell the Milam family that they remembered her well and thought of her over the years.

"We enjoyed her humor and she was spot on for being an excellent student," Farris wrote. "RIP, Pam."

Debbie Caldwell, who said she grew up in the same neighborhood as Milam, recalled her being “very pretty and sweet.” Kathy Hall Haller, one of Milam’s sorority sisters, described the time following the slaying as a very difficult one.

"This (news) conference brought me some closure," Haller wrote. "The police department did an amazing job. Rest in peace, Pam."

Watch Terre Haute Police Chief Shawn Keen talk about the Pamela Milam case below.

Milam, who commuted each day from her family's home to the university, was last seen by some of her Sigma Kappa sorority sisters when she went to move her car to a parking lot closer to the Lincoln quad, where the sorority had rooms, Keen said. Milam planned to stay on campus the weekend of her slaying to attend a number of sorority events being held.

Following the events the Friday night she disappeared, Milam told a couple of her sorority sisters that she would meet them a few minutes later at the quad, where they planned to eat after the night’s festivities.

Milam never showed up. She also failed to show up for an 8 a.m. shift Saturday morning at the library where she worked, Keen said.

The chief said Milam’s sister and her boyfriend became worried, as did her sorority sisters.

Two of the sorority members found her 1964 Pontiac LeMans around 7 p.m. that Saturday night, parked in a lot across from Lincoln quad, Keen said. They retrieved a flashlight from the sorority house and went back to the parking lot, where Milam's car was backed into a spot.

Photos from the crime scene show the car, with its license plate reading, “Jesus,” on the front.

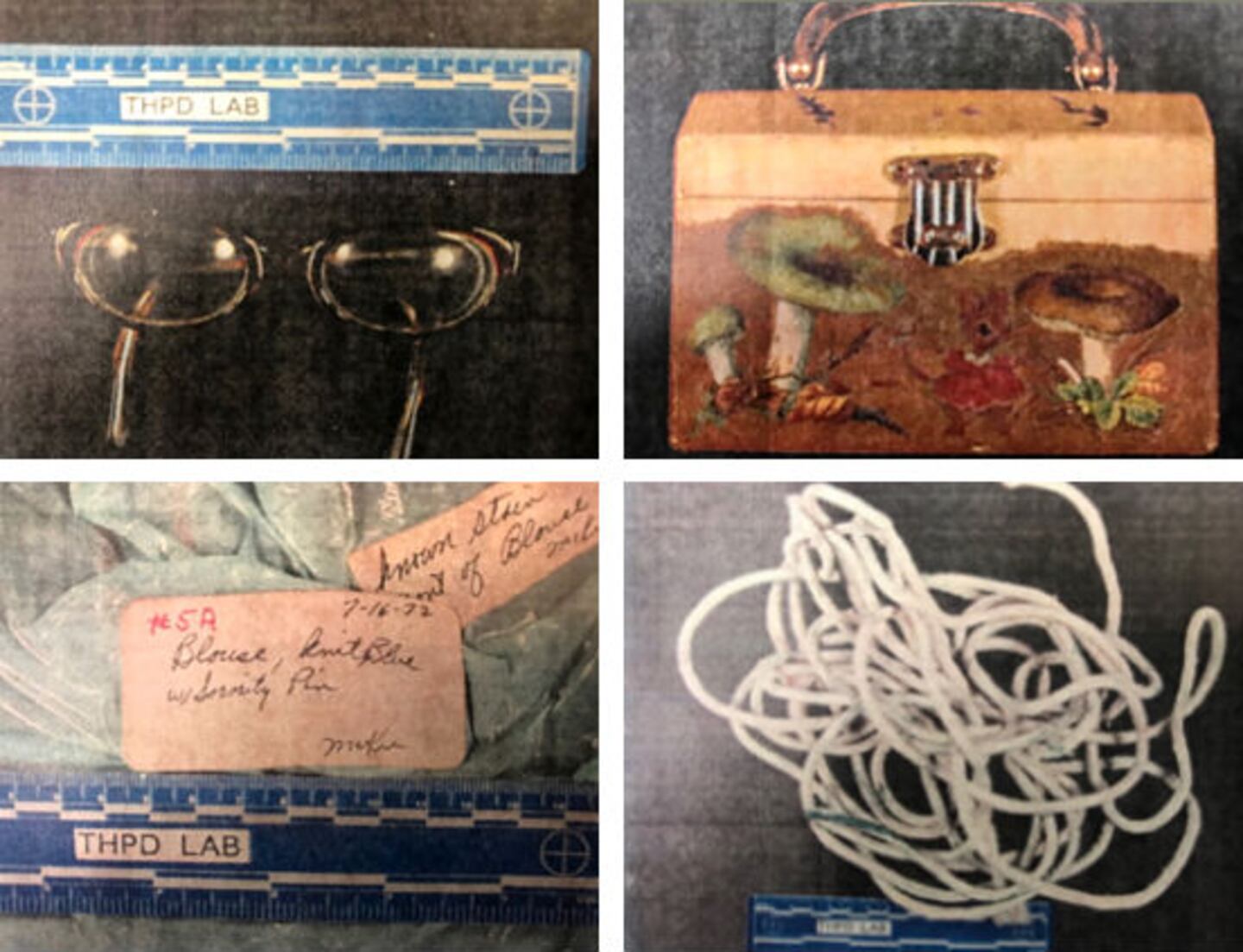

“The first thing they noticed were her glasses in the rear window of the car,” the chief said. “Her purse was later found in the back seat, passenger’s side.”

Sheila Milam and the siblings’ father, Charles Milam, arrived at the parking lot around 8:30 p.m.

"Her father has an extra set of keys to the car, and both he and Sheila get into the car," Keen said. "He removes her glasses and her purse, and then opens the trunk, where he discovers the body of his daughter."

Sara Deane Bishop wrote on Facebook that she was one of Pam Milam's sorority sisters and was with the family when they found her body.

“It has been a long almost 47 years, especially for Pam’s birth family and for her Sigma sisters,” Bishop wrote. “She has not been forgotten.”

Clothesline was used to bind Milam’s hands and to strangle her, Keen said. A cloth had been stuffed in her mouth.

Debris, including twigs, was found between her pants and her pantyhose, indicating her pants had been removed in a wooded area.

"This was significant to investigators to know this," the chief said.

Investigators at the time also noted a stain on her blouse, though technology in 1972 was unable to help them link it to a suspect. Milam also had a number of scratches and bruises on her face and elsewhere on her body, denoting a struggle.

Along with the clothesline recovered from the car was a roll of duct tape. Soil samples were also taken at the scene.

"They did a really good job at the time of processing the scene for both trace evidence and soil samples," Keen said. "But again, this is 1972 and forensics were not what they are today."

Keen said the items found in the car, including the clothesline and duct tape, were among items used to decorate one of the parties Milam had attended the night she was slain. She carried a box of the decorations with her as she left the events.

The items were tools of opportunity and were not brought to the scene by the killer. Keen said he believes Milam was a random victim and she and Hand happened upon one another.

Investigators had no witnesses to the slaying and no real descriptions of a suspect, the chief said. All men who had contact with Milam or had been identified as having been on campus at the time of her death were interviewed, and several polygraph exams were administered.

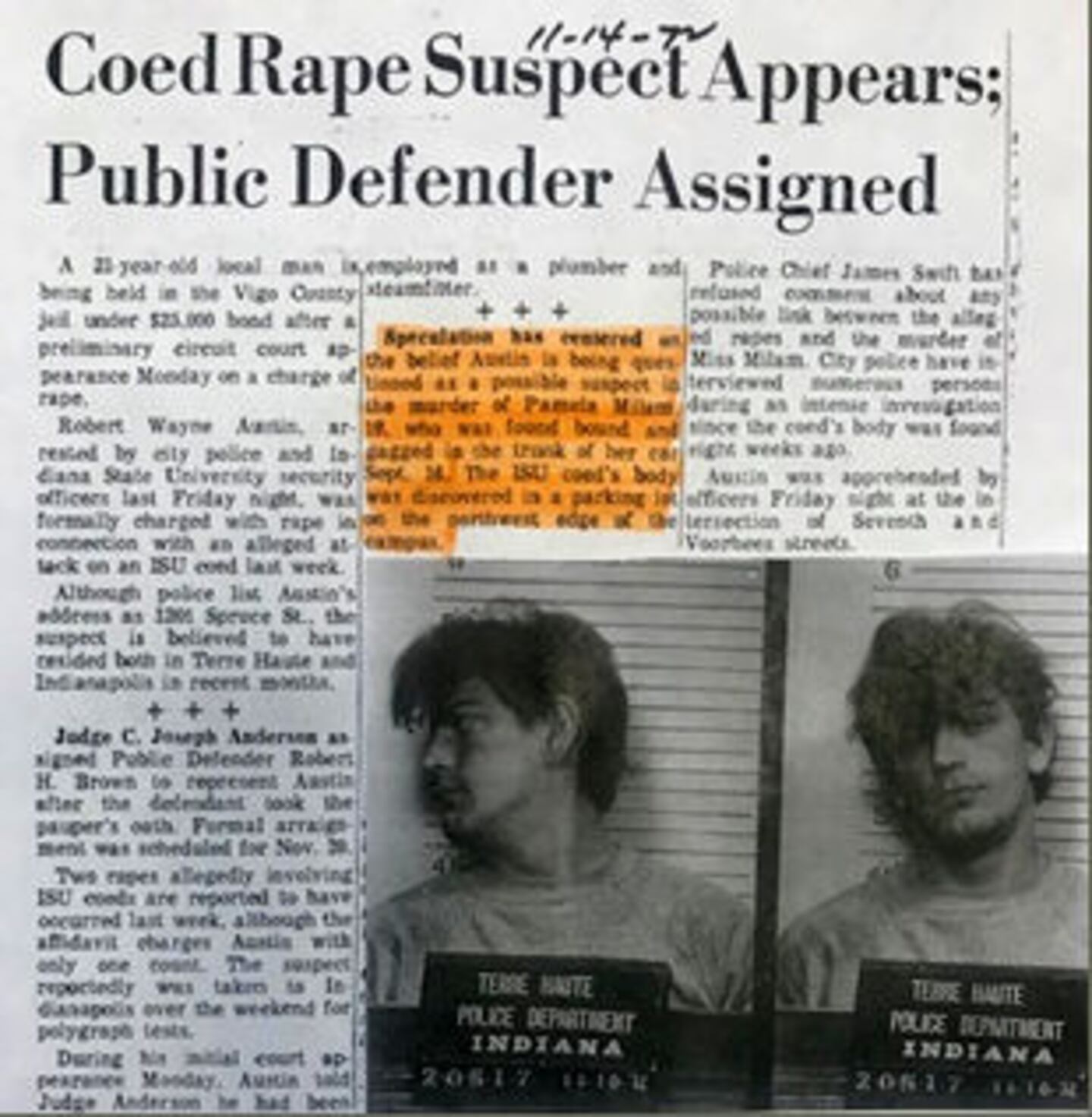

No real suspect was identified until seven weeks later, when a man named Robert Wayne Austin was arrested in connection with a string of abductions and rapes on the ISU campus. Austin abducted the other women and took them to a secluded area off campus, where he raped them. He then returned them to the university.

"For investigators at the time, they believed that Austin was responsible for this crime," Keen said. "How many predators could you possibly have in an eight-week period, in such a small area? So that's what they believed. A lot of the MO (modus operandi) was similar. They really believed he was their person."

Austin was convicted of rape, sodomy and kidnapping and given a life sentence in 1973, the chief said. Though he admitted to the crimes for which he was convicted, Austin denied killing Milam.

Detectives, still believing he was Milam’s killer, found themselves stalled in their investigation.

A new look at an old case

Keen said the Milam case remained dormant until 2001, around the time he became a detective. At that point, a fellow investigator working the cold case decided to test the evidence for DNA, which was becoming a bigger avenue for solving crimes.

Most of the evidence, not packaged very well at the time of the crime, was too degraded to provide a DNA profile. Milam’s stained blouse was the exception, Keen said.

"The next step is the obvious one to investigators," Keen said. "We need to get Mr. Austin's DNA profile."

Austin, who served about two decades of his life sentence before being paroled, was located by detectives, who obtained a genetic sample from him.

The DNA didn’t match.

“The belief since 1972 that he was responsible was wrong,” the chief said.

The killer's profile was entered into the FBI's Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, but failed to match any of the profiles in the system.

Keen said investigators, using new lighting sources unavailable in 1972, were able to detect a fingerprint on the lens of Milam's glasses. The print, along with two partial prints from Milam's car door, was submitted to the Automated Fingerprint Identification System, or AFIS. Detectives did not find a match.

"Again, in 2001, the investigator at the time did not have much more to go on than in 1972, other than now he could eliminate Robert Austin as the suspect in this case," Keen said.

The case got yet another fresh look in 2008, when Keen became chief of detectives and reopened a number of cold cases haunting Terre Haute. After assigning cases to his detectives, he assigned the Milam case to himself.

“I had no idea it would be another 11 years before we had a resolution to this,” Keen said. “But when I first opened up the case, I couldn’t stop reading it.”

The chief said he took the case file home with him that first weekend.

“My wife was really upset,” Keen said. “I had it strung all over the living room floor. Every piece of it represented one of the 56 males that were mentioned in the case file.”

Keen said one huge challenge was dealing with the time that had gone by since the crime, which was committed two years before he was born. Another was tracking down everyone who had been interviewed.

At the time of the murder, investigators collected only the person’s name, address and telephone number.

"Which, that's great in 1972, but not so great 40 years later if you want to try to find these people," Keen said.

The chief said he subpoenaed student records and used that information to look up what those people had been up to over the four decades since Milam was killed. Though a couple of promising leads were established, none of them panned out.

Touch DNA was also coming into fruition in 2008, so Keen had the clothesline used to bind and kill Milam retested for evidence. A partial profile obtained from the rope could not be eliminated as having come from the same person who left the stain on Milam’s blouse.

“I could use it to exclude other people, but what it also told me, and what I was interested in, was whether or not someone else was involved in this crime, other than just one male,” Keen said.

He said the results gave him confidence that only one person was involved.

Other things Keen did in 2008 to solve the case included putting Milam’s case on playing cards distributed to inmates by the Indiana Department of Corrections in the hope someone in prison might have information about her death.

In 2009, Keen started questioning the possibility of using familial DNA to find the suspect. At that time, what the use of familial DNA would entail was using the profiles in CODIS to find relatives of the person who left the evidence at the scene of Milam’s killing.

An Indiana state proposal to allow the method to be used by law enforcement fell through, Keen said. At the same time, none of the men named in the case file appeared to be responsible for the Milam murder.

“At nighttime, I would lay in my bed and I would use my phone and I would go through just anything, you know? Serial killers in the 70s. Anything that matched this,” he said.

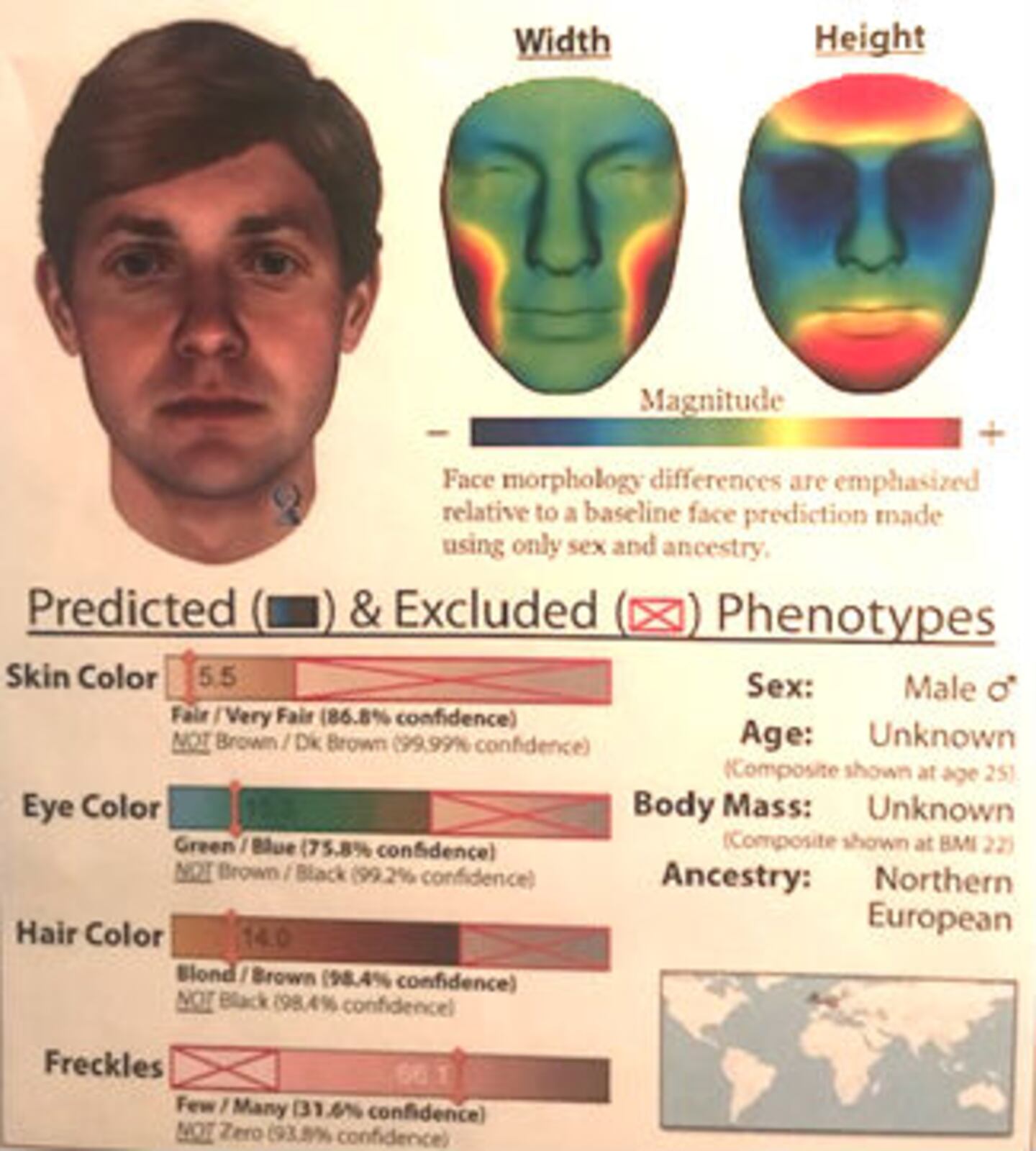

In 2017, phenotype testing became available, allowing investigators to predict the hair color, eye color and skin tone of the man who left the DNA at the crime scene. The profile indicated Keen was looking for a man with brown eyes, medium brown hair and intermediate to dark skin.

See an explanation of phenotyping below.

He also began expanding his search for the killer outside of the case file, Keen said. He pulled out 1,100 arrest reports between the time of the killing and the present day and went through them by hand, pulling out everyone with the physical characteristics established by the phenotype testing.

He also scoured the reports for people who had committed sex crimes, winnowing down the number of possible suspects to just over 100. Familial testing, now known as forensic genealogy, remained at the back of his mind, however.

In 2018, that led Keen to Parabon Nanolabs Inc., a Virginia-based company that offers the service to law enforcement agencies. Since the use of public genealogy websites to find a suspect in California's infamous Golden State Killer case last year, Parabon has helped agencies across the country name suspects in 55 cases, including two additional cases in which resolutions were announced this past week.

In one of those cases, the company helped Seattle police investigators identify a suspect in the 52-year-old murder of one of the department's own records clerks. Susan Galvin, 20, was found raped and strangled in a parking garage elevator in July 1967.

Parabon was able to link DNA evidence from the scene to Frank Wypych, a former soldier and security guard who died of diabetes complications in 1987. The match was confirmed when Wypych's body was exhumed and a DNA sample was obtained for direct comparison.

The Galvin murder is the oldest case genetic genealogy has solved thus far, Parabon said in a news release Wednesday.

In the second case, Christopher VanBuskirk, 46, of Goodyear, Arizona, was arrested April 29 and charged in a string of four rapes committed in San Diego between August and November of 1995. Another two rapes committed in Riverside County in March 2002 and November 2004 were found to be committed by the same man.

According to San Diego police officials, VanBuskirk, who allegedly raped the women at knifepoint, was identified through genealogy databases and the DNA samples of direct family members. VanBuskirk was extradited to San Diego County on Monday, jail records show.

Keen said he was interested in two of Parabon’s services: the company’s “Snapshot” composite profile, which provides a computer-generated composite sketch of what the DNA indicates a person might look like, and its genetic genealogy.

The chief said Parabon does not run a suspect’s DNA directly through sites like Ancestry or 23andMe, but runs it through GEDMatch, a public site on which users who upload their genetic information are informed beforehand that law enforcement officials may access their data.

“Everyone that submits to GEDMatch does so voluntarily,” Keen said.

Keen said the first sample he gave to Parabon did not provide a big enough DNA profile. He then had to weigh giving the company a larger sample of the killer’s DNA versus the chance that an even better crime-solving technique could pop up a few years down the road.

“That really weighed heavily on me that night,” Keen said. “But the more I thought about it: It’s been 46 years. I really think it’s significant. I really think we could solve this case.”

The larger sample produced a much better result, Keen said. Unfortunately, Parabon’s phenotype report gave him a completely opposite description of the killer than that supplied by the first lab.

Keen said that moment was the lowest he’d been while on the investigation.

“I’d just spent three months relying on somebody telling me the person has brown hair and brown eyes and medium complexion,” Keen said. “This report says fair, very fair, eye color green/blue, hair blond to brown. For three months, I’d just went through and excluded all these people from my list.”

Unsure what to make of the new phenotype profile, Keen focused his attention on the genetic genealogy. Parabon used the DNA from Milam’s blouse to find an Indiana woman distantly related to the suspect.

The genealogist worked her way back through the family tree and found two possible suspects. One of the men was too young -- about 13 at the time of Milam’s slaying, Keen said.

Attention on the second man led Keen to several elderly relatives who helped him build their family tree. They also gave DNA samples which Keen submitted to Parabon.

The results showed the men were close relatives of the suspect. Further investigation led to one man’s nephew -- Jeffrey Lynn Hand.

“What we would learn about Mr. Hand is quite a bit,” Keen said.

A violent life and a violent end

Hand was 24 years old and living in Evansville, about two hours south of Terre Haute, nine months after Milam’s killing when he was arrested for kidnapping a couple hitchhiking in Terre Haute. According to news clippings provided by Keen, Carol and Jeffrey Wayne Thomas, both 22, were taken to Hand’s home in rural Gibson County, north of Evansville, and tied up at gunpoint.

Hand was accused of taking Jeffrey Thomas to a separate location in Posey County and killing him while Thomas’ hands were tied behind his back. Carol Thomas managed to escape the grain bin in which she was being held and seek help while Hand was away.

He was taken into custody after returning to his home and finding deputies waiting for him. He later led detectives to Jeffrey Thomas’ body, the news reports said.

“He died a very violent death, being shot and stabbed,” Keen said of Thomas.

Hand went on trial for Thomas’ murder in October 1973, but was found not guilty by reason of insanity, the chief said.

While awaiting trial on a kidnapping charge, Hand nearly killed another inmate in the county jail, so he was moved to a state prison.

In June 1976, Hand’s attorney, arguing that he should have also been found not guilty by reason of insanity on the kidnapping charge and that civil commitment papers were not filed in a timely manner, got his client released from prison, Keen said.

0

Hand next showed up on police radar in January 1978 when Kokomo police officers shot and killed him during a gunfight following an attempted abduction. Another news clipping Keen provided at Monday’s news conference said the abduction, at gunpoint, took place when Hand forced a woman into his car outside a shopping center.

Bystanders called 911 and a Howard County sheriff’s deputy driving through the area responded, the clipping said. The deputy cut off Hand’s escape, chased him on foot into an alley and apprehended him.

When the deputy reached into his patrol car for his radio, Hand pulled a handgun and twice shot the deputy, who survived.

Kokomo patrol officers arrived and continued the foot pursuit, shooting Hand three times as he ran and crawled through a railyard and under a freight car. Hand collapsed on the other side of the freight car and died.

Keen said that, upon learning Hand’s history, he went back and looked at Parabon’s composite image of the suspect. The image is eerily close to what Hand looked like in the time frame of the slayings.

The chief said his skepticism vanished.

“They were right -- the blue eyes, the blond hair,” Keen said. “They were right. The other lab was wrong, or they didn’t have enough to do an accurate account.”

Keen said that was when the case began coming together after more than four decades.

“It’s just unbelievable that this is possible,” he said. “Even the part in his hair is right, and that’s just a guess.”

1

Keen said he then turned to Hand’s widow and his three children to finalize the investigation. The widow told Keen she and her then-husband lived in Terre Haute in 1970 and 1971, at which time Hand worked for the U.S. Postal Service.

They were no longer living there in 1972, but Hand worked for a Chicago-based record company.

“He would deliver those throughout Illinois and Indiana to the different shops that needed their records stocked,” Keen said. “That could have been what brought him here. I will note that, in both crimes, when he picked up the hitchhikers and when Pam was killed, we have a weekend and we have late night.”

Hand’s widow and two sons provided DNA samples that definitively linked him to Milam’s murder, Keen said.

“They went out of their way to be helpful,” Keen said. “I was very up-front with them about what we were doing, and they went out of their way. They didn’t have to, but they did. ‘You want my DNA? If this is going to help some family, you can have it.’”

Sanford also praised Hand’s family members for their cooperation with the investigation of her sister’s murder.

“It must have been so hard to hear what their relative had done,” she said.

Keen said he met last week with Vigo County Chief Deputy Rob Roberts, who reviewed the evidence and said there would have been sufficient evidence to file charges against Hand if he were alive.

Hand would now be 70 years old.

Keen said he believes Hand was able to fit in on the university campus where he killed Milam because of his age at the time. He was 23 when Milam was slain.

The chief ended his presentation by displaying a photo of Milam, saying that her sister, Sheila, has called him at least once a year for the past 11 years, hoping to hear positive news of a resolution to the case.

“She’s honestly what kept me motivated in this case, because like I said, there were times that I did not....” he said, trailing off. “The brown eyes, brown hair thing -- that was honesty my lowest point.”

Keen said the Milam family is as responsible as anyone for getting the case solved.

Sanford said her sister was taken from them in one of the cruelest ways possible.

“No one wants to hear the words, ‘Your child has been murdered.’ But in our case, it was my father who told me,” she said. “It was my sister, Sheila, who had to tell our mom.

“No family should ever have to go through that.”

Cox Media Group